This winter Hunter Research completed an archaeological investigation at the Randolph Friends Meeting House Cemetery in Randolph, Morris County, paving the way for a new parking lot and pathway. The extraordinarily well-preserved frame meeting house, built circa 1758, is New Jersey’s oldest extant colonial wood-frame Quaker meeting house and the oldest standing structure built as a house of worship in Morris County. The Randolph Friends Meeting House & Cemetery Association have embarked upon a project to provide some much needed parking on the property within the bounds of the cemetery on the site of a former wagon shed. Although no grave markers stood in this section of the cemetery, there remained a possibility that graves were present, as Quaker burials typically went unmarked up until the mid-19th century.

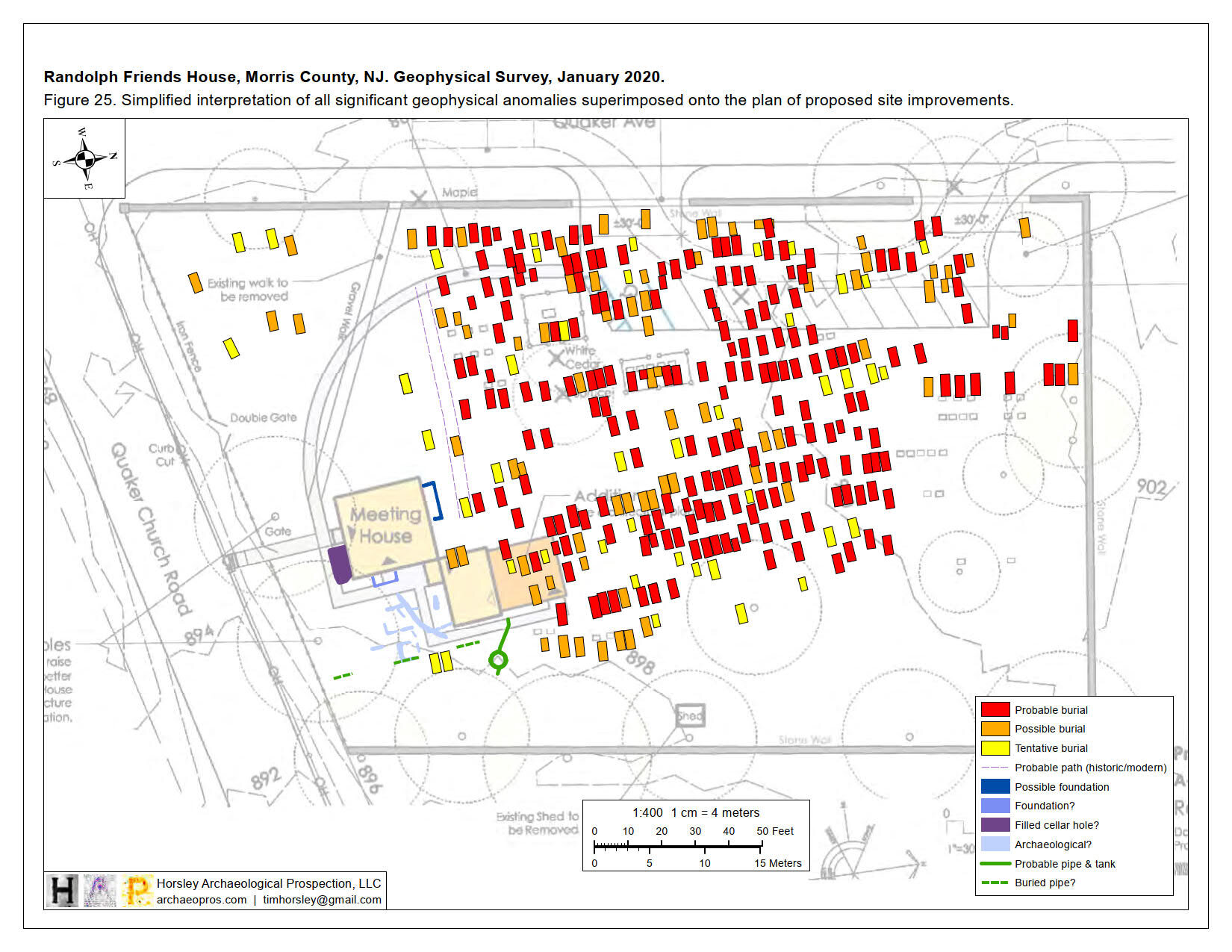

Archaeological investigation began with a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey conducted by Dr. Tim Horsley. This work identified over 70 anomalies interpreted as potential grave shafts within the limits of the proposed parking lot and associated pathway. A grant was obtained from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust Fund to support archaeological “ground truthing” of the geophysical findings. In January of 2021 a Hunter Research field crew, assisted by an excavation contractor who has worked with us for over 30 years, carefully opened up three large trenches within the parking lot and pathway footprints. After removing the topsoil and scraping off the surface of the underlying subsoil through a combination of machine and manual excavation, a total of 43 potential grave shafts were exposed as rectangular outlines with a different soil color, many of which correlated with the GPR anomalies identified by Dr. Horsley.

Identifying a grave shaft does not necessarily mean that anyone is “home,” so to speak.In an effort to determine the presence, depth and condition of human remains within these grave shafts, ten were selected for exploratory excavation.Of these, nine were confirmed to be grave shafts through the presence of human and/or coffin remains.Unfortunately, the survival of skeletal material was poor; most burials had less than 25% of the skeleton remaining, due largely to the slightly acidic soils.Despite this poor preservation, shroud pins and even burial shroud fragments were identified.Of the nine burials, five were judged to be those of children.The skeletal remains were not removed, but instead exposed, documented in place, and carefully reburied along with any associated grave goods. These investigations have provided useful insights into late 18th- and 19th-century Quaker burial practices while giving the Association the information they need to design their parking lot and pathway without impacting the cemetery’s residents lying in repose.