Cemetery, burial ground, graveyard – what is the difference? Each refers to hallowed ground harboring our discarded human shells. As we go about our daily lives, these places of final repose may seem like fixtures in the landscape – pillars of the community that never change. But study any burying ground in depth and you will be struck by how transient such places are, how fleeting the afterlife can be.

In recent years, Hunter Research has specialized in the study of cemeteries – documenting them in their current state; remote-sensing them to delineate their boundaries and pinpoint graves; excavating them to make way for development; and making recommendations as to how best to preserve them for future generations. Yet, the physical fabric of all cemeteries – the memorials above ground and the bodily remains below – inexorably fades and its management is but a tale of short-term maintenance to stave off long-term decay.

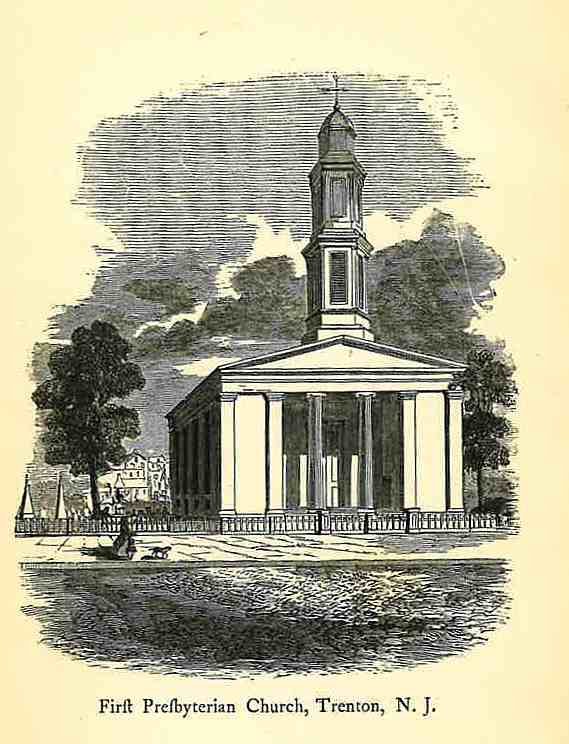

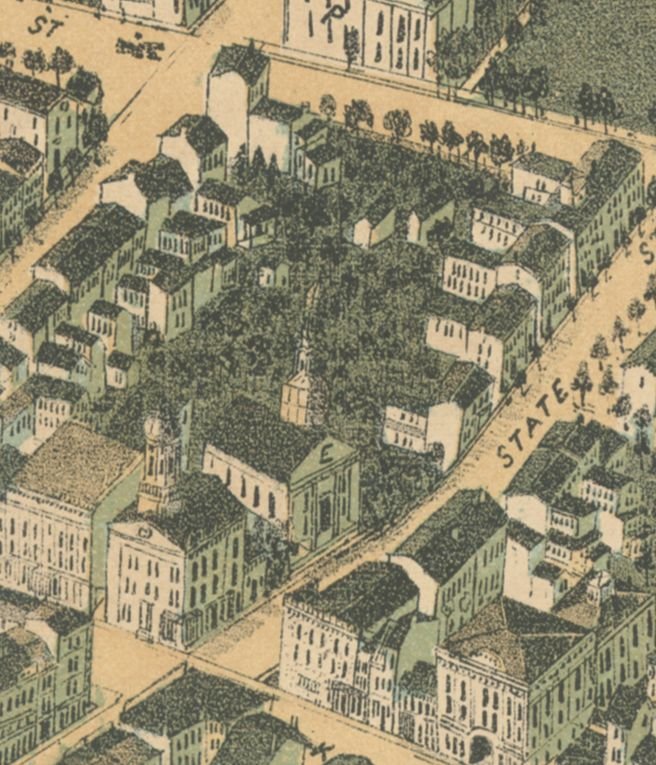

Over the past two years, with funding support from the New Jersey Historic Trust, Hunter Research has completed preservation plans for two of downtown Trenton’s most venerable graveyards, both now closed for burying: the First Presbyterian Cemetery on East State Street and the non-sectarian Mercer Cemetery across from the Trenton train station. We have wrestled mightily with the challenge of how to protect and honor these cemeteries in the face of erosion by the weather and pollution, and damage from vandalism and neglect.

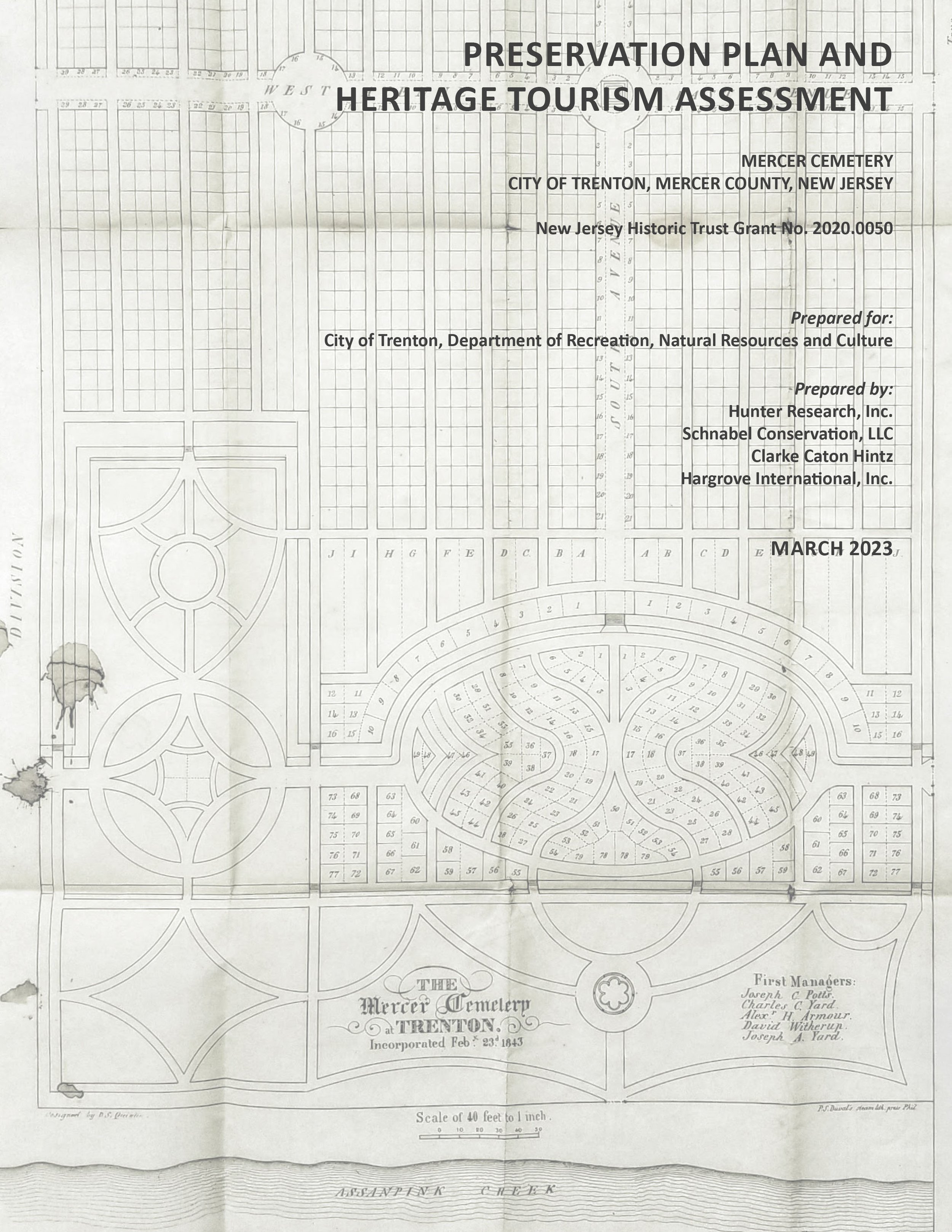

The First Presbyterian and Mercer Cemeteries are quite different. The First Presbyterian Cemetery was in use from the late 1720s until around 1900, and today sports roughly 200 grave markers and 16 monuments, although in excess of 500 interments are thought to have been made over the centuries. Many of the grave markers have been moved from their original locations. The Mercer Cemetery was established in the early 1840s, filled up rapidly in the later 19th century and burying continued intermittently into the 1970s. There are close to 3,000 grave markers and monuments and most are in their original locations.

The two preservation plans are founded on a comprehensive documentation exercise, including a conditions assessment of each grave marker and monument, that resulted in the creation of a cemetery-specific geographic information system (CGIS). The ultimate goal of each CGIS is to make the cemetery data accessible online in the form of a geodatabase and an interactive map. Each plan uses the CGIS as a basis for formulating prioritized treatment recommendations for the preservation and maintenance of the cemetery and for deriving rough cost estimates for their repair and restoration. The Mercer Cemetery study also includes a heritage tourism plan which considers the feasibility of incorporating the cemetery into Trenton’s plans for revitalizing the city around its history assets.

Both preservation plans are currently under client and New Jersey Historic Trust review, but will hopefully be accessible on our website within a few months. We acknowledge the considerable assistance of Schnabel Conservation, LLC and Horsley Archaeological Prospection, LLC in our study of the First Presbyterian Cemetery, and of Schnabel Conservation, LLC, Clarke Caton Hintz, Hargrove International, Inc. and Richard F. Veit, Ph.D. in our study of Mercer Cemetery.

![21082 Figure 4.12 - EU 6, 7, 8, 9 Plan View [Landscape 11x17]_1.png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1683044600597-RAVE0SVB6WJ22GRZ8IP8/21082+Figure+4.12+-+EU+6%2C+7%2C+8%2C+9+Plan+View+%5BLandscape+11x17%5D_1.png)

![21082 Figure 4.14 - EU 6 NW Profile and EU 9 SE, SW and NW Profiles [Landscape 11x17]_1.png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1683044600626-2STHIDUPURQFTA0GL7S7/21082+Figure+4.14+-+EU+6+NW+Profile+and+EU+9+SE%2C+SW+and+NW+Profiles+%5BLandscape+11x17%5D_1.png)

![21079 Figure 2.25x. Old Swedes Church] 1850 to 1860 service-pnp-ppmsca-39900-39946v.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1675716414674-92VD2VKDXGVQDZJVCWPD/21079+Figure+2.25x.+Old+Swedes+Church%5D+1850+to+1860+service-pnp-ppmsca-39900-39946v.jpg)